Chief John Ross and the Legacy of Art - Part I

Emery Benson & Jennifer Crutchfield with contributions from Vicki Rozema

Our team at National Park Partners works to champion the conservation of the natural, historic, and cultural resources of our National Parks, engaging current and future generations in preserving and promoting the stories of these national treasures. As a small team, NPP is grateful for a partnership with the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga History Department, that allows student interns to join us in this important work. This year Emery Benson, a history major and rising Junior from Maryville, Tennessee, worked with our team and, in this assignment, explored the Trail of Tears through this portrait of Chief John Ross. Join Emery for this three-part blog series as he introduces us to conversations and insights sparked by an almost 200-year-old work of art.

Jennifer Crutchfield, National Park Partners

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which included furthering his goal to remove all Cherokee people to lands west of the Mississippi and opening the Cherokee lands for development which then still represented a country within a country.’ Over the course of eight years, a majority of the roughly 16,00 Cherokees were routed from their homes, culminating in thousands marched by General Winfield Scott’s troops to new lands under harsh, often deadly, conditions.

Cherokee removal is a tale of factions, assassinations, broken trust, and the immutable tension between pragmatism and idealism. Opposition to removal among the Cherokee Nation was fierce and legislators and politicians were equally passionate in their fight against the legislation.

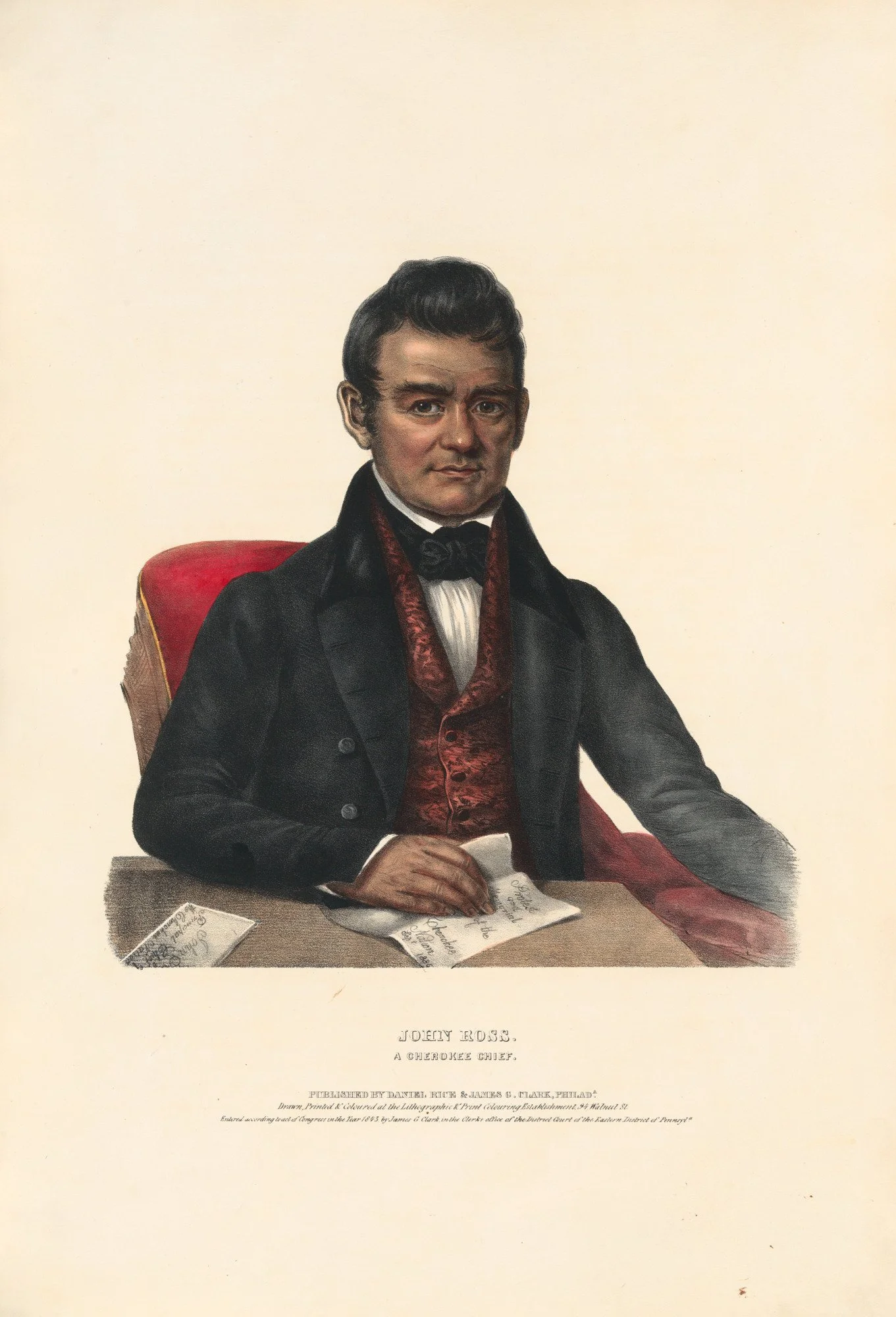

Portrait of Chief John Ross, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute

The story of Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears can be interpreted from an unusual source, a unique portrait of John Ross, 1790 - 1866, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Hanging in the Smithsonian Institute, this portrait spurred questions and research that led to correspondence with the Smithsonian, inspiring a better understanding of Cherokee factions during the 1830s, and the little-known story of one U.S. politician’s attempt to preserve a record of the Indian nations he recognized were on the verge of being removed from their ancestral homes.

This portrait appears normal at first glance, one in a long series, though a careful observer might notice a few curious details. Chief John Ross holds a document called Protest and Memorial of the Cherokee Nation, dated September 1836. Additionally, the portrait’s description on the Smithsonian website attributes it to Alfred Hoffy, an artist contracted to copy Charles Bird King’s original painting. Who is Alfred Hoffy? Charles King? To figure out the Ross portrait’s artist, and, equally as important, who commissioned it, we looked to the Smithsonian, the Thomas L. McKenney legacy, and McKenney and James Hall's History of the Indian Tribes of North America, a publication in which the portraits are said to have appeared.

Thomas McKenney served as the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Trade, which later became the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830 and is identified as having commissioned Charles King to paint portraits of leaders of many Indian delegationswhen they visited Washington. McKenney apparently recognized that the Native way of life was under threat and wished to preserve a record of indigenous life and culture.

McKenney believed that Indians should remain on their lands but be firmly assimilated into the White Anglo-American culture, contrary to President Jackson’s assertion that Indians must be removed west of the Mississippi River. Charles King ultimately painted 143 portraits of various Indian leaders, including John Ross. In 1830, McKenney was removed from his position in the government, likely the result of disagreements with President Jackson. McKenney had displayed the portraits in the Bureau of Indian Affairs offices in anticipation of their inclusion in a book documenting the Indian nations of North America, an idea that ultimately became the tri-volume work, History of the Indian Tribes of North America. With McKenney no longer working for the government, he had to figure out a new method to continue his work.

Tune in next week for the second installment in this exploration of Chattanooga history!